New data: People with incarcerated loved ones have shorter life expectancies and poorer health

by Emily Widra, July 12, 2021

Locking up the most medically vulnerable people in our society has created a public health crisis not just inside prison walls,1 but in the outside community and across the country: The health of individuals, families, and entire communities is clearly associated with incarceration.

That’s according to a recent study from a team of researchers from the University of California – Los Angeles, University of Massachusetts – Amherst, Yale School of Medicine, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Duke University, and Washington University in St. Louis, which reveals how strongly incarceration is associated with family member health and well-being, as well as with racial disparities in health and mortality.

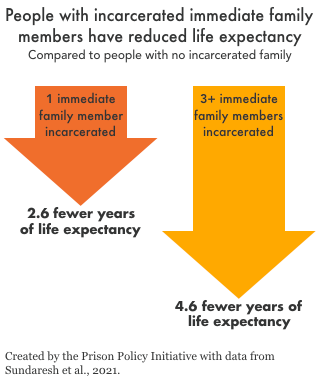

In the study, Exposure to family member incarceration and adult well-being in the United States, researchers found that people who have an incarcerated or formerly incarcerated family member2 consistently rate their health and well-being lower than those without a family history of incarceration, and have an estimated 2.6 years shorter life expectancy than those with no incarcerated family members, even when adjusted for demographic characteristics like race, household income, gender, and age.

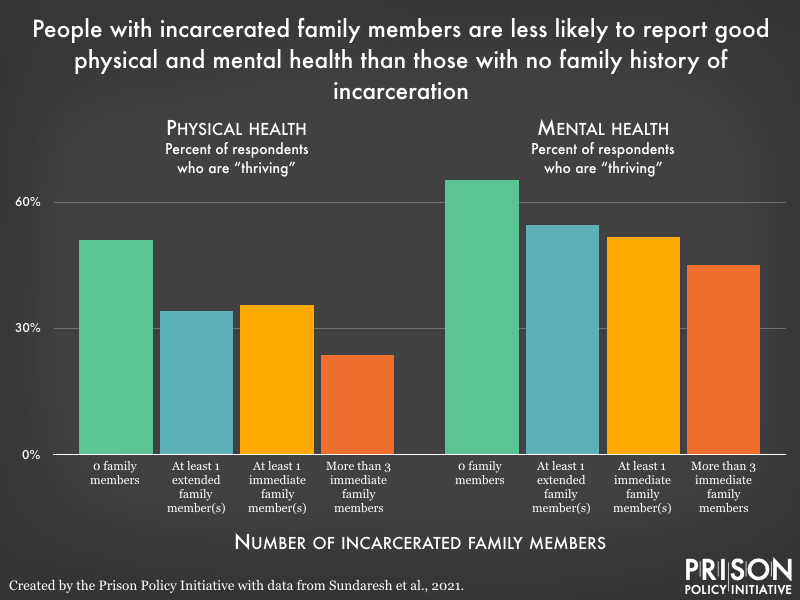

This groundbreaking study was based on a nationally representative sample3 of individuals who rated their own physical health, mental health, social well-being, and spiritual well-being on a scale from zero to ten. Their responses were then scored to categorize the respondents as “thriving,” “surviving,” or “suffering” in each area, as well as in a comprehensive and holistic category of “overall well-being.” Based on the health differences reported by people with and without incarcerated family members, the researchers then estimated the changes in life expectancy associated with family member incarceration.

The researchers broke down their results by demographic categories, allowing us to see how the impact of family incarceration on well-being varies by age, gender, race and ethnicity, education level, household income, housing type, marital status, family size, and the respondent’s own history of incarceration or substance use disorders. The results were further broken down to how the effects of family incarceration differ depending on whether it’s an immediate family member4 or extended family member5 that was incarcerated, on the length of their incarceration, and on the number of incarcerated family members (the impacts were greatest for those with multiple incarcerated immediate family members).

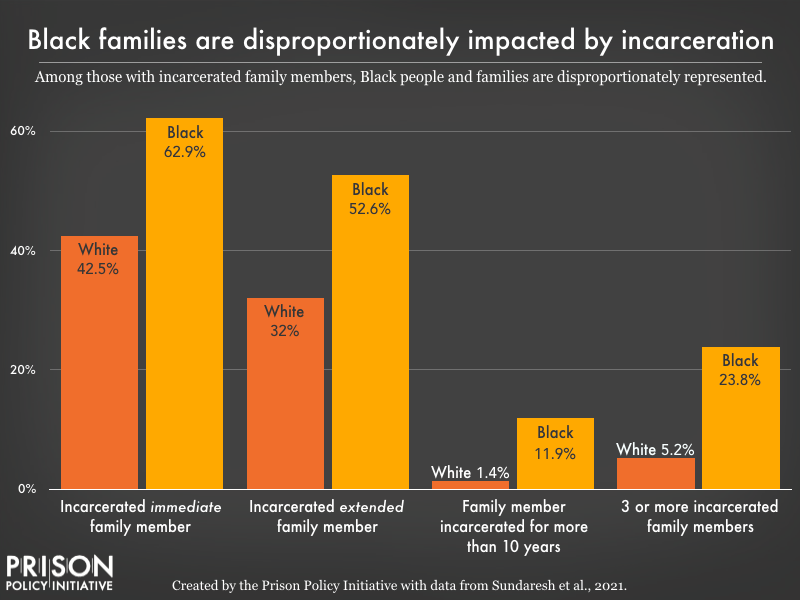

In this briefing, we discuss two types of analyses conducted by the researchers. First, the researchers analyzed the demographic differences between people with incarcerated family members and people without incarcerated family members, giving a clearer picture of just who is most likely to experience family member incarceration. Their analysis shows stark racial disparities in family incarceration, as well as differences in physical and mental health between those who have incarcerated family members and those who do not.

Second, the researchers isolated the impact of incarceration on life expectancy, by presenting a statistical analysis of their findings that accounted for differences in age, gender, race and ethnicity, education level, household income, housing type, marital status, family size, and the respondent’s own history of incarceration or substance use.

People with incarcerated family members have poorer health outcomes

We already know that having a family member incarcerated can cause financial instability, reduce social support, and increase the burden on caregivers. Studies have also shown that women with incarcerated partners experience depression, hypertension (high blood pressure), and diabetes at higher rates than those with non-incarcerated partners, and children with incarcerated parents are at increased risk for mental health problems and substance use disorders, which have long-term impacts on health.

This new study, however, is the first to look at how the incarceration of a family member is associated with overall well-being, using a comprehensive, holistic measure of well-being (see sidebar for more details on measuring well-being). And the findings show that people with incarcerated immediate family members – such as a parent, partner, child, or sibling – are less likely to report good physical and mental health and less likely to rate as “thriving” in terms of overall well-being, all else being equal.7 A “thriving” score overall or in any subcategory (like physical health or mental health) is significant, because it is strongly correlated with fewer health problems, fewer sick days, fewer negative emotions (worry, stress, sadness, anger) and more positive emotions (enjoyment, interest, happiness, respect).8

A demographic analysis of people with incarcerated family members

This study provides further evidence of the strong overlap between overcriminalized communities and people experiencing disparities in health care. The study found that individuals with any immediate or extended family member incarcerated were more likely to be Black, live in a low-income household, have a history of a substance use disorder, and have a personal history of incarceration.

That Black families are disproportionately likely to have had a family member locked up is unsurprising, given the well-documented racism in the criminal justice system and the rampant racial disparities in prisons and jails. Compared to white respondents, Black respondents were more than twice as likely to have multiple family members incarcerated and over eight times more likely to have had an immediate family member incarcerated for at least a decade.9

Incarceration reduces life expectancy of family members, not just those locked up

A 2016 study from Professor Christopher Wildeman found that the sheer magnitude of mass incarceration in the United States has shortened the overall U.S. life expectancy by 2 years, and that each year in prison reduces an individual’s life expectancy by about 2 years.

This new study from 2021 shows that not only does incarceration impact the population-level life expectancy and the life expectancy of individuals behind bars, but it also impacts families and communities. People with one immediate family member who has ever been incarcerated lose 2.6 years of life expectancy, and people with more than 3 immediate family members with incarceration histories lose almost two times as many years (4.6 years) off their life expectancies, regardless of age, race/ethnicity, gender, income level, housing type, family size, or personal history of incarceration or substance use.

This study is the first to identify the extent to which incarceration is associated with the overall well-being and lifespan of an incarcerated person’s children, spouses, parents, and grandparents. Nationally, an estimated 45% of people have an immediate family member who has been incarcerated and 35% of people have an extended family member with a history of incarceration–suggesting that mass incarceration harms the health and well being of tens of millions of Americans, regardless of their personal involvement in the justice system. The study’s authors conclude that decarceration efforts could have wide-ranging outcomes in terms of national health and life expectancy. Their findings confirm what people with incarcerated loved ones already know: far from keeping people safe, prisons and jails are public health disasters, and closing them is imperative to public health.

Footnotes

-

People incarcerated in prisons and jails are more likely to have health conditions that shorten their life expectancy, like lung disease, heart conditions, diabetes, renal or liver disease, and other immunocompromising conditions. ↩

-

For the purposes of discussing this study, “an incarcerated family member” refers to an immediate or extended family member that was incarcerated at any time. These data do not differentiate between currently or formerly incarcerated. ↩

-

The sample used in this study was a cross-sectional, nationally representative sample of respondents from the 2018 Family History of Incarceration Survey. 2,815 individual respondents were included in the analysis of this study. ↩

-

Immediate family members are defined as parents, partners, siblings, or children. ↩

-

Extended family members are defined as grandparents, aunts or uncles, nieces or nephews, cousins, parents- or siblings-in-law, or godparents. ↩

-

For more details about the Cantril Scale and the Life Evaluation Index, see Arora, A., et al., 2016. ↩

-

The researchers note that the association between immediate family member incarceration and “thriving” remained statistically significant after adjusting for age, gender, race/ethnicity, education level, household income, housing type, marital status, family size, and the individual respondents’ history of incarceration or substance use disorders. The association between extended family member incarceration and “thriving” was no longer statistically significant after adjusting for respondents’ own incarceration history and immediate family incarceration history. ↩

-

For more details about the scoring system for the Cantril Scale, see Understanding How Gallup Uses the Cantril Scale. ↩

-

These findings discussed here are not adjusted to account for age, gender, ethnicity, education level, household income, housing type, marital status, family size, and the respondent’s own history of incarceration or substance use disorders. Rather, these findings are a comparison between two groups of respondents: the percentage of white respondents with incarcerated family members and the percent of Black respondents with incarcerated family members. ↩