Food insecurity is rising, and incarceration puts families at risk

Several studies show that formerly incarcerated people - and the children of currently incarcerated people - are at especially high risk of experiencing food insecurity.

by Jenny Landon and Alexi Jones, February 10, 2021

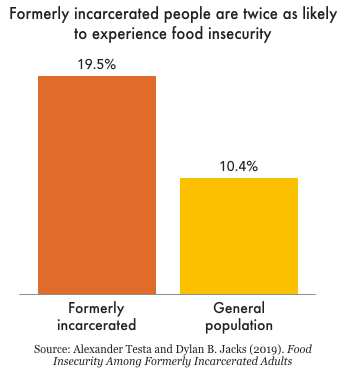

Food insecurity is an often-overlooked consequence of incarceration, and it can’t be separated from the more well-known problems of homelessness and unemployment. While the estimates vary somewhat, researchers consistently find that food insecurity is more common among formerly incarcerated people — and families with an incarcerated parent — than among the general population:

- In a 2013 survey of recently released individuals in three states, 91% of respondents reported food insecurity, and 37% reported not having eaten for an entire day because they could not afford food.

- A 2019 study found that 20% of formerly incarcerated people report suffering from food insecurity — double that of the general population — with even higher rates among formerly incarcerated women and Black individuals.

- Young children who live with their father before his incarceration are three times as likely to experience food insecurity, according to a study focused on the impact of paternal incarceration.

- Finally, a 2012 study found that the incarceration of either parent increases the likelihood of food insecurity for adults and households with children by up to 15 percentage points.

These last two studies offer further, direct evidence of how incarceration punishes entire families and communities, not just people who are locked up. Most incarcerated people are parents; their absence while incarcerated – and the barriers they face when they come home – have ramifications for their entire families, particularly children. The potentially severe and lifelong consequences of experiencing food insecurity in childhood are among the many injustices visited upon the families and communities most impacted by mass incarceration.

The high levels of food insecurity among formerly incarcerated people also underscores the difficulty of reentry, and the lasting, life-threatening effects of incarceration. Apart from the obvious policy choice of incarcerating fewer people, states and counties must provide more robust support for recently released people. States that still limit access to food programs like SNAP (or food stamps) because of former convictions must immediately abandon this discriminatory practice, and invest in infrastructure so that formerly incarcerated people and food-insecure families have access to transportation, housing, and employment opportunities.